لقد بدأت دراسة اللغة العربية – في اللهجة العامية المصرية – بنفسي في العام 2017 عبر وضع نفسي في ظروف حياتية يومية وبالاستعانة أيضًا بدروس خاصة ما زلت أخذها ثلاث مرات في الأسبوع مع معلمة مصرية. لم أكن يومًا وسط زملاء يدرسون اللغة لأقارن بيني وبينهم، ولم أجرِ اختبارات لأعرف أو لأنال درجة أكاديمية معترف بها تشير لمستوايّ باللغة العربية. لقد كانت معايريّ لقياس تقدمي مختلفة كليةً؛ كنت أسأل نفسي كلما شرحت لصاحب المطعم تفاصيل الساندوتش الذي أريده هل الساندوتش اليوم ألذ من البارحة؟ فلو كان ألذ سيشير ذلك إلى أنني تقدمت في اللغة. وحين أطلب بلطف من أحدهم أن يتحرك لأنه يدوس على قدمي؛ هل تحرك قبل أن أتأذى

معظم من قابلتهم كلما أخبرتهم بأنني أتعلم اللغة العربية أكون في انتظار ردة فعل معينة “إنتي العربي بتاعك كويس قد ايه؟” ولا أعرف في كل مرة ما الإجابة المناسبة. بينما أعلم خارج الأكاديمية ليستُ متأكدةٌ كيف يجب أنْ أقيمَ مقدوري في اللغة العربية. رغبتهم في معرفة عن لغتي العربية كافية لتحقيق أي هدفٍ

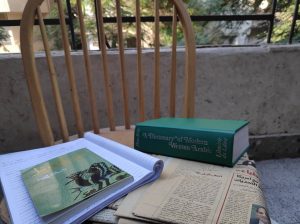

بعدما بدأت بدراسة اللغة العربية الفصحى منذ ستة شهور، صرت أبقي عيني على موارد التعليم التي يمكن أستفيد منهم، وعلى المعايير التي تشير إليها هؤلاء، و التي يمكن تنظر من تلميذ اللغة العربية. هذه الإيام عندما أجلس لأقرأ نصًا باللغة العربية أثناء دراستي، ستجد دومًا بجانبي قاموسًا ضخمًا أخضر اللون. هذا هو قاموس “Hans Wehr English to Arabic Dictionary” الذي يعد من أهم القواميس المتخصصة لدراسة اللغة العربية للأجانب. يعطيني هذا القاموس لمحة عن تاريخ دراسة اللغة العربية و المعايير الاستشراقية، على رأي ادوارد سعيد المؤثر، التي كانت تحدد “كفية” محررات تلاميذ اللغة الأجنبية في الماضي

لقد كان “Hans Wehr” قد أعد هذا القاموس للحزب الشيوعي القومي الألماني، المعروف بإسم “النازيون” في أربعينات القرن العشرين. وترجم بعد ذلك إلى الإنجليزية في أواخر العقد السادس من القرن العشرين. كانَ تحالف المانيا مع الدول العربية في صالح الحزب النازي، بوجهة نظر “Wehr”. ولقد قام “Wehr” بتجميع خلاصة وافية من المصطلحات والمفردات لتحقيق هدفه السياسي؛ حيث كان يصب عمله في ترجمة السيرة الذاتية لهتلر إلى اللغة العربية؛ التي تربط تجربة هتلر الشخصية بمعاداة السامية

يعكس القاموس عقيدة التي أصادف بها الكثير في محاولتي تعليم اللغة. في وجهة نظر النازيين، كانت اللغة العربية آلة في مشروعهم الفكري. قد كانت ألمانيا تسعى لزيادة السلطة وتأتي إليها حلفاء أقوياء لتجميد قواتها قصاد تحالف المعرض. في مقابل هذا، ظهرت اللغة العربية وسيلة لتجاوز عن حدود أوروبا ويشتد حكمهم فيما وراء قاراتهم

لكن لم تكن الاستشراقيين الالمانيين من أوائل الدول ليوظف اللغة العربية من أجل تنفيذ هدفهم سياسي؛ إذ أتت منافستهم للمنصب الرئاسي بين دول أوروبا كخطوةٍ جديدةٍ في السبقة الاستعمارية التي وصلت في فجر القرن العشرين بالهرولة إلى أفريقيا. كما حددَ إدوارد سعيد في كتابه “الاستشراق” كانَ نابوليون الذي قد مهدُ طريق ، الذي كانَ “Wehr” يقلده لاحقا بعد مئتي سنة

أعطى سعيد لنابليون الفضل الأصلي في استخدام اللغة بهذا الشكل المدبر. أصبحَت القوةُ الناعمةُ هذه جبهةً في غزو نابليون لمصر عام ١٨٩٨. قبل أن يحتلها عسكريًا بوقتٍ طويلٍ، كانَ نابليون يعدّ ترسانته المعرفية ليحاول أن يوثق ويبوّب الثقافةِ الشرقيةِ وليستوعبَها في النهاية تحت سيطرة الإمبراطور الفرنسي

“فمنذ اللحظات الأولى التي ظهر فيها الجيش الفرنسي على الأفق المصري، بذل بونابرت قصارى جهده لإقناع المسلمين بقوله إننا نحن المسلمون الحقيقون، على نحو ما جاء في الإعلان الذي وزعه يوم ٦ يوليو ١٧٩٨ على أهالي الاسكندرية” كتبَ سعيد. علقَ إيضًا المؤرخ المصري عبد الرحمن الجبرتي عن استعانة نابليون بالعلماء في إدارة اتصالاته مع الأهالي. وحاولَ نابليون في كل مكان أن يثبت أنه يحارب في سبيل الإسلام، و كان كل ما يقوله يترجم إلى الأسلوب العربي القرآني

هذا رغم أنه لم يوجه اهتمامه لتوطيد التفاهم بين الدولة الفرنسية والدولة المصرية، ولكن شكلَت معرفته والترجمة إلى اللغة العربية جزء في “المهمة الحضارية،” التي نبعت من إيمان نابليون في تفوق فرنسا الحضاري، وحقها في الهيمنة على مصر وغيرها من الدول

بعد أن دخلَت قوات نابليون إلى مصر، أمر بونابرت فريق العلماء في معهد مصر بالبدء بالبحث المكثف من أجل تأليف كتاب “وصف مصر”. أسس نابليون هذا المعهد قبل أن يغزو مصر بوقت طويل من أجل تكوين الجبهة المعرفية من استعماره

توضح مقدمة هذا الكتاب الضخم المنشور في ثلاثة وعشرين مجلدًا بأنه وبخلاف ما تدعيه فرنسا بأن هدفها كان تطوير المعرفة وتوطيد التفاهم مع الدولة المصرية، إلا أن هدفها الحقيقي كان السيطرة الكاملة على مجريات العالم. بينما مصر واللغة العربية بحد ذاتهما لم يكونا سوى أدوات لتقريب فرنسا من هدفها المطلق. وما يؤكد ذلك قول أمين المعهد بأنه: “من اللائق إذن لذلك البلد أن يجتذب اهتمام مشاهير الأمراء الذين يتحكمون في مصائر الأمم

ورغم أن الغاية السياسية لبعض دول العالم الأول لم تعد واضحة كما كانت في حقبة بونابرت، ولكنها تظهر في بعض الأحيان في مناسبات عفوية. كزلة لسان الرئيس الفرنسي ايمانويل ماكرون عندما ذكر بأن هنالك مشكلة “حضارية” في افريقيا. أما من جهته رئيس الوزراء البريطاني الحالي، بوريس جونسن، فلقد كتب مقال من ٨٠٠ كلمة ليقول بأن مشكلة أوغندا الأساسية اليوم ليست استعمار بريطانيا لها، بل بأنها لم تعد تستعمرها لهذه اللحظة! وهو ما يبيّن بأن دراسة اللغة العربية في الغرب ما زالت حتى الآن وسيلة للهيمنة والسيطرة السياسية على الدول الناطقة بالعربية

يعد البرنامج الدراسي الذي يدرس في “معهد قاصد” في عمان في الأردن، على سبيل المثال لا الحصر، من أقوى وأهم البرامج التعليمية الباهظة الثمن التي تدرس اللغة العربية للأجانب. في حين أن معظم المنح، إذ لم يكن جميعها، التي تمنح للطلبة مقدمة من القطاع الحكومي في دول كبرى، كأميركا و…، تشترط على الطلبة العودة بعد إنهاء تعليمهم للعمل في القطاع الأمني في تلك الحكومات، كالعمل في وكالة المخابرات الأمريكية (CIA) ووزارة الدفاع ووزارة الخارجية والقطاع الدبلوماسي بدل أن يكون لها أهداف أخرى تجارية مثلًا

أنا سعيدة أني أستطعت التجنب عن الجامعات والمؤسسات الرسمية باعتقادي لا زال يتأثرون ايديولوجية استشراقية، و عبر دراستي اللغة العربية مع استعانة منحة “John Speak” أستطيع التقدم بطريقة آخرى. قالت لي في مرة واحدة صديقة لي، ناقدة افلام هنا في القاهرة، التي أعلمت الكثيرا عن اللغة وغيرها منها، أن يشبه تعليم اللغة تعليم الطبخ. نبدأ بالأشياء الأساسية، الساندويتشات، الرز بالقوام الكامل، ولا معجن ولا ناشف، مثلما في اللغة يمكن أولا أن تنطق الحروف، و تفعل الأشكال الجديدة على شفتيك. كذلك لا تظل اللغة محاصرة في كتب أخضر اللون، ولا في أروقة السلطة، ولكن نحيَّها بأفواهنا و ننطقها على ألسنتنا

I first started studying the Egyptian Arabic dialect in 2017. I learnt both with my wonderful Egyptian teacher, and by putting myself in a variety of awkward life situations. I remember a particularly embarrassing moment when a driver stopped a minibus at the side of a busy highway, and shouted that all the passengers must get out because someone hadn’t paid. Faltering from the back seat, I admitted my guilt, as I had come out without the correct change and had been too nervous to attempt an explanation. But since beginning to learn the language, not once have I been surrounded by classmates with whom to compare myself, nor have I been formally examined to receive an academic grade for my language skills. I have measured myself against different standards instead. After a detailed explanation to the owner of my local restaurant, I would ask myself in the morning if my breakfast sandwiches had turned out tastier than yesterday’s. And when I needed to ask politely if the person standing on my foot could move, could I ensure this happened fast enough to prevent substantial pain?

When I explain to people that I have spent nearly two and a half years now in attempting to improve my language skills, I can often anticipate their response. “So, how good is your Arabic?” I have never been able to think of an appropriate response. Studying outside of academia and institutions, I am uncertain how to quantify my ability to communicate. What is my Arabic supposed to be good enough for?

Over the last six months, as I have begun to study formal Arabic thanks to a grant from the John Speak Trust, I have increasingly looked out for the resources and standards that might be expected of an Arabic learner. Nowadays, you will rarely find me studying without the company of a large green hardback; “The Hans Wehr English to Arabic Dictionary”

The dictionary, which is considered one of the most useful resources for those learning Arabic as a second language, gives me a glimpse into the past of Arabic language studies, and the orientalist standards which have historically defined “how good” one’s language skills ought to be as a foreign learner.

Hans Wehr compiled his German-Arabic dictionary in the forties for the German National Socialist Party, better known as the Nazis. It was later translated into English. Wehr believed that an alliance between Germany and the Arabic speaking nations was in the Nazi Party’s interests, and he began to work on a comprehensive collection of vocabulary and terms to support his political goals, as well as to work on a translation of Hitler’s autobiography, and the anti-semitic ideology it laid out.

The dictionary reflects an attitude which I come across often in my attempts to learn more about Arabic. For Germany at the time, the Arabic language added another weapon to their arsenal. Germany was attempting to aggregate power in order to gather a greater force than the opposition coalition. In the interests of such a project, Arabic was a means to overstep the borders of Europe, and to spread their power into the neighboring continents of Africa and Central Asia.

And Germany’s early twentieth century orientalists were not the first to make the attempt. They were merely entering into an existing competition for primacy among Europe’s leading nations; their project was just another step in the race for empire which culminated at the beginning of the twentieth century in the “scramble for Africa.” As Edward Said wrote in his seminal exposition, “Orientalism,” it was Napoleon who really laid the groundwork for the cultural project which Wehr would continue 100 years later.

Said credits Napoleon with the first such calculated use of academic Arabic language studies. This kind of soft power became a front in his invasion of Egypt in 1797. Long before his military invasion, Napoleon had begun to collect and taxonomise knowledge of culture in the Middle East and North Africa, and to bring it within the scope of the French imperial project.

Said writes, “From the first moment that the Annee d’Egypte appeared on the Egyptian horizon, every effort was made to convince the Muslims that “nous sommes les vrais musulmans,” as Bonaparte’s proclamation of July 2 1798 put it to the people of Alexandria.”

Despite this, Napoleon had little genuine interest in engaging with Egypt on a cultural level. Knowledge of Egypt and translation into Arabic formed instead a crucial part of his “mission civilisatrice,” which sprang from a conviction in the inherent civilizational superiority of France, and it’s right to dominate not only Egypt, but countries far beyond.

After Napoleon’s forces entered Egypt, Bonaparte gave orders to a team of academics from the Institut d’Egypte, which he himself had founded in the lead up to his invasion, commanding them to begin research towards a hefty tome called “The Description of Egypt.”

The 23 volumes of the Description clarify the intentions behind France’s attempts to develop a greater knowledge of Egypt, intentions which can accurately be described as an aim for world domination. As such, Egypt and the Arabic language itself were only tools to bring France closer to her ultimate goal. “It is proper for this country to attract the attention of illustrious princes who rule the destiny of nations,” wrote the secretary of France’s Institut D’Egypt Jean Baptiste Fourier, in his introduction to the Description.

While the political ends of the world’s leading countries are no longer quite so blatant as they were in Napoleon’s era, yet evidence of a similar attitude can still be found. Macron’s slip of the tongue, for example, when he accused the African continent of having a “civilizational problem,” or even from our own Prime Minister Boris Johnson, in an 800 word slip of the pen, in which he claimed that Uganda’s problems have no relation to British imperialism, but rather stem from the fact that Uganda is no longer a British colony.

But to return to the history of Arabic language studies, we can still find remnants of the same approach lingering in the institutions offering education to those wishing to learn Arabic as a second language. Those searching for funding to study at the Qasid Institute in Amman, Jordan, which is partnered with top western universities such as Oxford and Harvard, have the option of the Boren Scholarship, which requires its winners to return after their studies to work for the US State Department, or in a branch of the US intelligence services. It is still difficult for most people to access such education, without its ultimately feeding back into the political projects of those who view Arabic as a “strategic” language, one which will contribute to the US or UK’s political interests abroad.

I am thankful that studying Arabic outside of universities and formal institutions has allowed me to progress in my own way, and to avoid the orientalist attitude which still lingers in more formal channels of education. A film-critic friend of mine here in Cairo, from whom I have already learned so much about Arabic as well as many other things, once told me that learning a language should be like learning to cook. You start with the daily basics, sandwiches, perfectly textured rice that’s neither mushy nor too hard and dry. Making the right sounds, forming the right shapes with your tongue and lips. Pleases and thank yous. Yums and smacking of the lips. That way, rather than being trapped in green books and halled-up in the decision-making chambers of world powers, the words can live in the mouths of their speakers, on tongues and plates and in streets and shops where the words are pronounced.